Farming History - introduction

|  |

A short history of farming

Farming not only produces the food we eat, it created the

countryside we live in and is changing it, even as you read these

words. The classic British landscape of small fields, farms and

villages linked by sunken lanes was carved out of the Wildwood which once

covered much of Britain by people earning a living from the land, first by

hunting and then by farming. How did this happen?

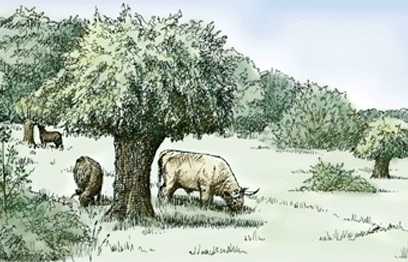

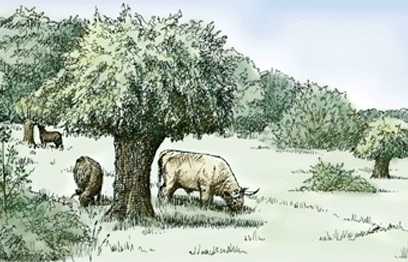

As the ice retreated north at the end of the most recent

glaciation, 15,000 years ago, it left behind a landscape of tundra and

rock. At this time the North Sea did not exist: plants, animals and people

could travel on dry land from mainland Europe to Britain. Trees moved north

across this land bridge and, as the climate warmed, a forest spread over

much of lowland Britain. Deer, elk, aurochs (the wild ox, ancestor of

domestic cattle), wolves and other animals followed the trees, and

groups of Mesolithic hunters followed their quarry into Britain.

As the ice retreated north at the end of the most recent

glaciation, 15,000 years ago, it left behind a landscape of tundra and

rock. At this time the North Sea did not exist: plants, animals and people

could travel on dry land from mainland Europe to Britain. Trees moved north

across this land bridge and, as the climate warmed, a forest spread over

much of lowland Britain. Deer, elk, aurochs (the wild ox, ancestor of

domestic cattle), wolves and other animals followed the trees, and

groups of Mesolithic hunters followed their quarry into Britain.  These hunters began the long process

of clearing the forest by using flint axes and fire to create grassy

clearings in which deer and other grazing animals would come to feed.

(There is evidence that upland peat moors such as the Yorkshire Moors

formed after these clearances, nearly 10,000 years ago.) Their movements

across the landscape established tracks and routes such as the Icknield

Way.

These hunters began the long process

of clearing the forest by using flint axes and fire to create grassy

clearings in which deer and other grazing animals would come to feed.

(There is evidence that upland peat moors such as the Yorkshire Moors

formed after these clearances, nearly 10,000 years ago.) Their movements

across the landscape established tracks and routes such as the Icknield

Way.

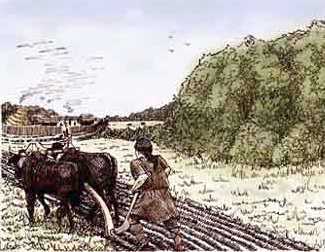

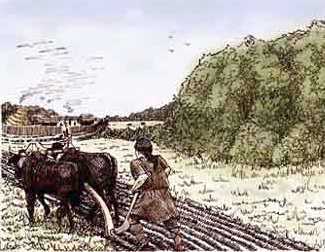

The idea of Agriculture and the technology needed to keep domestic

animals and to plant, harvest and process crops spread slowly north

and west across Europe from Greece, reaching the coast of France and

Belgium about 6,000 years ago. The first signs of farming in Britain

soon appeared, ranging from the the seeds of emmer and einkhorn

wheats and barley to the marks left by an ard (the first plough) and

the stone querns on which grain was ground to flour. It would have

been relatively easy to cultivate the areas of grassland which had

been grazed by deer and other wild game, but more land was always

needed as yields fell without fertilisers and the population grew.

Sharp polished stone axes felled trees faster than flint, and the

surrounding undergrowth was burnt or browsed to death by livestock

and wild game. Crops were grown for a few years on the new fields

then, when yields dropped, the farmers moved on to clear more of the

forest. Grazing animals prevented the forest reclaiming the old

fields while their droppings fertilised the soil; early farmers would

soon have learned the value of manure and the need to rest fields as

fallow to recover fertility.

More food meant

more people could live in the same place for longer, so settlements formed.

Permanent boundaries marking land holdings first appeared in the Bronze

Age, 4,000 years ago. In the Iron Age people were living in permanent

houses, farming land divided into fields and storing their harvest for use

through the year. By the time the Romans arrived, large parts of southeast

England were already a patchwork of hedged fields, with farmsteads and

villages connected by tracks and droveways.

More food meant

more people could live in the same place for longer, so settlements formed.

Permanent boundaries marking land holdings first appeared in the Bronze

Age, 4,000 years ago. In the Iron Age people were living in permanent

houses, farming land divided into fields and storing their harvest for use

through the year. By the time the Romans arrived, large parts of southeast

England were already a patchwork of hedged fields, with farmsteads and

villages connected by tracks and droveways.

Sarah Wroot 2000

As the ice retreated north at the end of the most recent

glaciation, 15,000 years ago, it left behind a landscape of tundra and

rock. At this time the North Sea did not exist: plants, animals and people

could travel on dry land from mainland Europe to Britain. Trees moved north

across this land bridge and, as the climate warmed, a forest spread over

much of lowland Britain. Deer, elk, aurochs (the wild ox, ancestor of

domestic cattle), wolves and other animals followed the trees, and

groups of Mesolithic hunters followed their quarry into Britain.

As the ice retreated north at the end of the most recent

glaciation, 15,000 years ago, it left behind a landscape of tundra and

rock. At this time the North Sea did not exist: plants, animals and people

could travel on dry land from mainland Europe to Britain. Trees moved north

across this land bridge and, as the climate warmed, a forest spread over

much of lowland Britain. Deer, elk, aurochs (the wild ox, ancestor of

domestic cattle), wolves and other animals followed the trees, and

groups of Mesolithic hunters followed their quarry into Britain.  These hunters began the long process

of clearing the forest by using flint axes and fire to create grassy

clearings in which deer and other grazing animals would come to feed.

(There is evidence that upland peat moors such as the Yorkshire Moors

formed after these clearances, nearly 10,000 years ago.) Their movements

across the landscape established tracks and routes such as the Icknield

Way.

These hunters began the long process

of clearing the forest by using flint axes and fire to create grassy

clearings in which deer and other grazing animals would come to feed.

(There is evidence that upland peat moors such as the Yorkshire Moors

formed after these clearances, nearly 10,000 years ago.) Their movements

across the landscape established tracks and routes such as the Icknield

Way.

More food meant

more people could live in the same place for longer, so settlements formed.

Permanent boundaries marking land holdings first appeared in the Bronze

Age, 4,000 years ago. In the Iron Age people were living in permanent

houses, farming land divided into fields and storing their harvest for use

through the year. By the time the Romans arrived, large parts of southeast

England were already a patchwork of hedged fields, with farmsteads and

villages connected by tracks and droveways.

More food meant

more people could live in the same place for longer, so settlements formed.

Permanent boundaries marking land holdings first appeared in the Bronze

Age, 4,000 years ago. In the Iron Age people were living in permanent

houses, farming land divided into fields and storing their harvest for use

through the year. By the time the Romans arrived, large parts of southeast

England were already a patchwork of hedged fields, with farmsteads and

villages connected by tracks and droveways.